I’ve just activated the emergency button on my Apple Watch with a shaky finger, and it has already alerted my sleeping son. (Hopefully!)

It’s December 2019, Covid has not raised its ugly head in the west yet, but I still think I am dying.

This can’t be — my life can’t be over so soon — I cannot die of a heart attack at 56 years old, I think as I try to sit up.

It’s 1:37 in the morning, I feel like I’ve run a marathon, and my stupid watch is making it worse by alerting me over and over again that “your heart rate is above 150 while resting.

“I know, goddammit.” I bark at the watch’s tiny square screen that’s too small to read without my glasses, stressing myself out even further. Next, the watch will tell me to breathe or stand up or something — sometimes, I think the alerts are the reason for my stress. Christ, my chest hurts like hell.

I sit on the edge of my bed, and I start imagining all the things that could be wrong with me — how I’m going to die so young — making my heart race even faster still. Another urgent alert about heart rate, but I can hear my son coming over the thundering blood pressure in my ears.

My middle son Alex, a former live guard, certified in CPR, bursts into my bedroom still in his pajamas, (well actually his underwear and a workout shirt), assessing the situation as he moves in closer — all serious and business-like. For a moment, I forget about my situation — a proud father of who he is and what he has become. Then my anxious brain squirts poisonous thought into my brain: what will happen if I die before his wedding or miss my youngest’s high school graduation?”

Seeing my state — sweaty forehead — wide-eyed in terror, my son’s convinced he’s going to have to revive me from a heart attack, but as he gets closer, he squints and says, “What wrong pops? Describe it to me.”

“Heart racing — chest pain — can’t breathe — feel like crap.” I blurt, trying to be as concise as possible, like the fake doctors on Grays Anatomy who can magically diagnose within seconds of seeing a patient.

“We’ll heart racing is good,” he says, “your not having a heart attack. Let’s get you calmed down.”

By now, there is so much adrenaline in my veins that I’m trembling, my arms are tingling, and this pain in my chest is crushing me from the inside. Worse yet, my wife and my two other sons have no idea this is happening; I might never get to hug them again; WTF.

But, of course, that doesn’t happen, obviously, or you wouldn’t be reading this book.

Just seeing my lifeguard son — so cool — so in control — calms me down, and over the next few hours, we get my heart rate in check so I can fall back asleep again.

And just like that, I get separated from my ordinary life

and thrust into a reality of the health care system.

Over the next couple of days, I had so many blood tests it was as if a medical vampire had made me his bitch. I had spots of missing chest hair from where sensors had been placed to perform EKGs and stress tests. They scanned my heart, stomach, and brain — every possible test my excellent health insurance would pay for.

On the fourth week of this, my doctor finally announces, “Well, good news, Kevin. You’re healthy as a horse.

“What… how…” I say, cutting him off mid-sentence, “that makes no sense.”

“It’s probably just sleep apnea or anxiety.”

Then his face turns all serious, “what’s a healthy person like you got to be anxious about?”

“Anxious about?” I practically scream, “besides the fact that my heart races when I sleep — I own a company that requires my everyday attention — I have teenagers in the house and everything that implies — I drink at least two pots of coffee every morning — then caffeine-infused tea all afternoon. I over-eat as a way to relax, then drink a bottle of wine or a couple of fingers of scotch to try to fall asleep. So not much, really, just one day in the life of an average dad.”

By now, the doctor has moved to the exit of the examination room; his escape route is planned in case I go fully postal. In Greys Anatomy, he would be calling for an Orderly to restrain me.

“I’m chronically exhausted,” I say, calming down a little, “I usually get about three to four hours of sleep per night. I think I’m starting to lose it.”

The doctor, an accommodating fellow, does what doctors do best — he prescribes Xanax and tells me to lose 20 lbs, then exits the room, leaving me there thinking about prepaying for burial plots, so my kids don’t have to deal with it after I die.

What was interesting about all the visits and tests, no one suggested that I quit drinking. Sure they ask if I drink on those little forms you have to fill out while you’re waiting. But the doctors almost seemed afraid to suggest that it might be a factor.

So I got one of those sleep apnea machines called a “continuous positive airway pressure” device or CPAP for short and took the Xanax to help me sleep. Of course, as the weeks turned into months, I drank more wine to help me forget about the impact of Covid 19 on my business and kid’s futures.

But my heart continued to race at night and sometimes even while watching TV or just for the heck of it mid-day and in meetings.

In November, just like every other person staying home during Covid, I was heavier than ever, drinking more than before and now taking Xanax periodically to fall asleep. Not a great situation — instead of improving, I was further down the rabbit hole of depression.

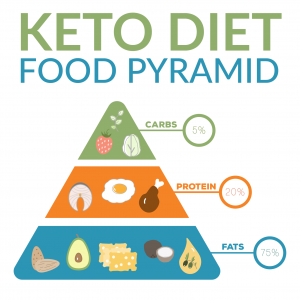

But not all the advice my doctor gave me was bad; the part about losing weight was a valid point. So, like so many others during Covid winter, I went on a diet. I watched Youtube videos on diet trends and soon discovered the Keto Method and, in particular, Thomas DeLauer’s Youtube channel.

Similar to Adkins but with some fascinating science behind it. And like all low-carb diets, wine was not on the menu. Damn!

But I felt like shit, was 30 lbs overweight, drinking too much, and not sleeping. Not a great combination of concerns, especially since Covid had a higher death rate among the unhealthy.

So I got started, giving myself 180 days to lower my weight to 180lbs. My own personal 180° method.

I loaded my fridge with protein and leafy vegetables, hid the sugar, and stopped buying booze.

Two weeks on Keto, I lost 3 lbs, and I had my first good night’s sleep in years. Like every other drinker, I didn’t attribute my success to the missing booze, God forbid. Instead, I attributed the good night’s sleep to the diet, telling everyone how the Keto diet was the greatest thing since bacon. But the truth of the matter was slapping me in the face; the booze was the cause of my racing heart.

So I used that same annoying Apple Watch to perform an experiment. I tracked my sleeping heart rate without alcohol and then with alcohol. Only to discover that the booze was definitely the cause of my sleep issues and the increased heart rate.

If I abstained from drinking for several nights, my sleep heart rate would be in the upper 50’s, but if I drank alcohol, it shot up to the ’70s. And worse yet, if I drank a few days in a row, it kept going up. I stopped the test after a night of 110 heartbeats per minute on average. What the Actual F%^$.

Suddenly, quitting drinking became my mission. What I wasn’t prepared for was how difficult leaving alcohol was going to be.

The words “non-drinker” have a weird sound to it because our current social situation demands that we drink alcohol along with everyone else. Booze, in our culture, is a rite of passage, a coming of age, and maybe even a requirement in some social circles.

Later on, you’ll learn that being a non-drinker is also a rite of passage, but for different reasons, more mature reasons. Being a non-drinker can make you stand out in society in a very positive way, a Badass Sober way, but back to the point: Booze has a high place in society while simultaneously destroying the fabric of family and friendships.

The term “abstainer” sounds like a disease that needs to be cured. For example, if you’re at a party or dinner event, and the host sees you abstaining without a drink in your hand, they are likely to make it their mission to get you a drink — to cure you of your illness. I’ve had friends actually ask me, “what is wrong with you.” When I’ve tried to abstain, they laugh at the idea of an Irishman without a drink in his hand.

Later on, in this book, you will learn how to deal with this situation 100% of the time, with no social repercussions, and even come out of it with a higher social status.

The term “Teetotaler” has a negative connotation; almost a swear word — used in a derogatory manner — where the person with the title of teetotaler is an outcast from the tribe. If you are a teetotaler, you must have been a drunk; therefore, you must have had a drinking problem. The problem with teetotalers is that we remind others of their drinking problems. We remind others that they have a struggle with alcohol. No drinker likes a teetotaler in their midst because they are like an x-lover in the room, constantly reminding them of their failings in life.

Later in this book, you will learn how to be a teetotaler and not be judgmental of those who still drink. How to be a positive influence without rubbing their nose in it. How to lead by example, not tell people what to do.

Not long ago, it was cool to smoke, even though we knew it caused cancer, changed our voices, and made us smell of tobacco.

Yet today, we still think, being able to “hold our liquor” is a good thing. Having liver damage, broken families, and feeling like shit in the morning is normal. Spending considerable parts of our income at the bar while struggling to pay off credit cards is acceptable. We think it’s ok that our liquor bill at dinner is more than the meal, that it’s a rite of passage as an adult to pay double to eat.

But I believe, being a “non-drinker” could be a badge of honor instead of a social mishap.

I believe, being an “abstainer” is a sign of strength and willpower that others do not possess.

I pity those who cannot become a “teetotaler” and break the bonds of alcohol—that’s why I’m sharing this very personal information about myself and my journey to quit alcohol.

In the 1800s, a group of people believed in teetotaling so much that they signed their names, followed by a lowercase t. Like how a Ph.D. boasts about their eight years in college by signing MD or Ph.D. at the end of their name — teetotalers signed theirs with a (t). It signified that they were totally alcohol-free as in total t. Or as it has become over the years’ — teetotaler.

I believe it takes a real BADASS to thumb your nose to social pressure and do what you think is suitable for yourself, your family, and your body.

Welcome to the world of BADASS and SOBER, where you can live as a non-drinking, an abstaining total (t) person and be a better human for it.